Integrating Schools of Thought – VirNet Mediation

Academic Mediation Research Review

Academic Models of Mediation: A Review

A paper published by Cory Harding at the University of Ottawa examined various academic models of conflict resolution and mediation. Harding found that a facilitative model–one where a mediator facilitates negotiated conversation and issues but does not offer much in the way of evaluation of issues or the merits of a party’s position–was the most common approach to mediation in the academic context. Factors such as flexibility, empowerment, and relationships between various stakeholders contributed to mediators’ choice to adapt and implement a facilitative model of mediation in the academic setting.

Mediation Models in Education: Replacing Traditional Legal Systems of Redress

Increasingly, schools, colleges, universities, and other organizations are adopting internal policies and practices related to mediation and alternative dispute resolution (ADR) as precursors and alternatives to traditional legal redress. While institutions cannot prevent suits in the court system, offering internal alternatives for redress may reduce the number and frequency of traditional lawsuits filed. Providing dispute resolution policies, procedures, and structures within the educational system not only potentially reduces litigation; it also provides students, teachers and faculty, administrators, and staff with a forum to address grievances and resolve conflict in a much less costly, protracted legal process.

Harding identifies what many educators, administrators, and academic or educational staff already know: the educational context exhibits a unique set of challenges due to various competing interests and the multi-faceted power dynamics between the school’s board or trustees, administration, faculty, staff, students, and other external constituents. External constituents range from parents and extended family members to community partners and donors. And unlike private businesses or other public and private organizations, educational institutions often feature distinctive hierarchies and departments or divisions that may exhibit competing and divergent goals, resource scarcity, and wholly different purposes based in disciplinary orientations and educational goals.

Conflict can emerge from multi-lateral power structures in education, because each sub-group within the educational system exercises a degree of status and authority due to its unique role and position within the institution. Faculty, administrators, and board members all exercise differing levels of authority and autonomy within the system, for example, which sometimes gives rise to competing interests and conflict. Harding notes that the limits to autonomy and authority in the educational context may also give rise to conflict, due to frustration, limitation, and competition.

Mediation Models in Education: Style and Form

The author of Mediation Models points out that roughly 25 styles of mediation exist, but three styles predominate in the literature. Facilitative, evaluative, and transformative mediation styles are by far the most common in both research and practice, including in the educational context.

Harding identifies many well-known styles of mediation cited in the literature before grouping them into three broad categories: problem-solving, facilitative, and relational styles of mediation. The individual styles of mediation include each of the following:

- Orchestrator or dealmaker style

- Bargaining and therapy approach

- Shuttle diplomacy

- Interventionist style

- Combination of facilitative and evaluative approaches

- Bargaining and integrative styles

- Counselor theory

- Negotiator approach

- Democratic style

- Formulation, manipulation, and reflective styles

- Directive and non-directive styles

- Neutral v. pressing styles

- Insight technique

- Transformative style

Problem-Solving Models. In the first of three categories of mediation, Harding includes the orchestrator and dealmaker; bargaining or therapy; dealmaking and shuttle diplomacy; and interventionist styles of mediation. Common characteristics of these styles include goal-oriented techniques designed to resolve issues in order to reach settlement. An orchestrator may take a more passive, non-directive style that provides a structure and context for the parties to reach their own agreement, whereas a dealmaker may shape and guide the conversation, applying pressure and goading the parties as they work toward settlement. (Importantly, these approaches assume some degree of equality between the parties in order to achieve mutually-beneficial outcomes).

Other problem-solving models may emphasize different aspects of conflict and conflict resolution, such as the emotional impact of the conflict (family therapy style mediation) or the significance and importance of engagement and compromise between the parties (shuttle diplomacy mediation). Finally, in an interventionist model, a highly-engaged and directive mediator guides the parties through structured interactions based on the mediator’s chosen topics and content areas.

Facilitative Models. Unlike problem-solving models, facilitative models emphasize relationships, communication, and the involvement of the parties in the mediation process. A facilitative mediator may look for mutual gains, understand party needs through active listening techniques, or attempt to remove the influence of the mediator as much as possible through passive conveyance of offers and other neutral actions designed to minimize any influence or interference in party negotiations.

Relational Models. Finally, relational models of mediation build on problem-solving and facilitative approaches that incorporate some level of communication analysis and relationship-building. Transformative mediation, for example, utilizes problem-solving techniques, but emphasizes holistic resolution and the incorporation of any and all relevant aspects of party perspective and experience as part of a negotiated settlement. The insight model draws on philosophical approaches to learning and the creation of meaning, similar to the sociological, symbolic interactionist approach to symbols and meaning construction. Transformative in nature, the insight model seeks to transform party perceptions of the other, shifting from a competitive, zero-sum approach to mutual understanding and cooperation due to insight gleaned from the mediation process itself.

Mediation Models in Education: Results

Harding designed a research study with multiple mediation practitioners and participants in mediation, followed by interviews and data collection. The overwhelming majority of participants described a facilitative style of mediation as the model that best suited the educational context, due to the level of sophistication of the parties, ability of participants to work with their counterparts, and relative depth of knowledge exhibited by the participants in the areas of dispute. A facilitative mediator in this context aims to enhance communication, clarify details, and assist the parties in reaching decisions and agreements.

While some participants viewed conflict the same within and outside of the educational context, others identified several aspects of the educational paradigm that make it unique and different from many other institutions, businesses, and organizations. Due to diverse interests and significant autonomy, many participants in educational or academic mediation may value empowerment and sense of responsibility for outcomes more highly as guiding principles of the mediation and expected outcomes. These factors may also enhance the long-term results of mediation, because participants are empowered to make decisions they are responsible for, unlike the outcomes of evaluative mediation where parties are guided more by the mediator’s perspective and input and may question the outcomes more as a result.

Ultimately, the relative autonomy and dynamic power structures of educational institutions align best with facilitative approaches that lean on the expertise, perspectives, and autonomy of participants. Empowerment and the value of reciprocal relationships stand out as implicit values within academic and educational mediation. The facilitative mediator who recognizes and supports these values in mediation will likely experience greater buy-in and participation, and agreements are more likely to persist once the mediator is no longer directly involved.

Citation

Harding, C. (2014). Mediation Models Used in Academic Settings. Department of Communication, University of Ottawa. https://ruor.uottawa.ca/bitstream/10393/31533/1/Harding_Cory_2014_research%20paper.pdf

Explore Mediation

Schedule a Call with Dr. Earwicker Today!

Learn MoreThe Effectiveness of Mediation and Peacekeeping in Active Conflicts: A Review

In light of the armed conflict in Israel and Palestine, many observers are asking what tools and approaches could be used to quell the active conflict and establish a framework for peace in the region. The protracted, long-standing conflict in Gaza and Israel eludes easy answers, and simplistic formulas for conflict resolution ring hollow; it would be naive to argue otherwise, given the history of failed peace efforts in the region. Nevertheless, recent research on mediation and peacekeeping suggests that mediation can be used effectively–with or without peacekeeping measures–to end hostilities and prevent the reoccurrence of armed conflicts.

Mediation and Peacekeeping: Tools for Conflict Resolution

A recent research publication in the Journal of Peace Research illustrates the value of both mediation and peacekeeping in conflict resolution, emphasizing the primary importance of mediation in ending active conflicts. Authors Govinda Clayton and Han Dorussen contend that while peacekeeping aims to prevent negotiated agreements from collapsing, the goal of mediation is to negotiate a resolution to conflict, empowering the various parties to reach consensus and determine the nature and scope of resolution.

The Relationship Between Mediation and Peacekeeping

Between the late 1940s and early 1980s, neither mediation nor peacekeeping were used extensively to address armed international or intra-national conflicts. As the authors point out, however, in the post-Cold War era, both have surged as diplomats and other leaders seek to end violent interstate conflicts.

In international or interstate conflicts between nations, mediation is rarely used in peacetime, whereas peacekeeping is generally used once a settlement has been negotiated and the armed conflict have ended. The use of peacekeeping strategies in Kashmir during active conflict stands out as an exception to this rule. At the same time, intrastate conflicts–civil wars and the like–differ from interstate conflicts and peacekeeping missions, and the application of mediation and peacekeeping differs significantly for intrastate conflicts. Their application will be limited here to interstate or international conflicts.

Ultimately, the authors conclude that while mediation–not peacekeeping–is key to ending armed conflict, both can work together in complementary fashion to more effectively reduce and end conflict. However, peacekeeping alone does not have a significant impact on ending hostilities in an armed conflict.

Defining Mediation & Peacekeeping

The goal of mediation in armed military conflict is to engineer a negotiated settlement to hostilities. Parties mediate a conflict when they accept the assistance of a third-party mediator to resolve the underlying dispute without resorting to physical force, violence, or legal authority. See Bercovitch, Anagnoson & Willie, (1991).

Mediation methods may include facilitation of information exchange, designing and constructing new processes and procedures, or manipulation through positive and negative inducement. Beardsley et al. (2006). As with any mediation practice, mediation in interstate conflict seeks to understand parties’ underlying interests in order to improve communication and resolution of concerns, moving the parties toward a negotiated solution. See Stedman (1997).

Peacekeeping, on the other hand, functions primarily as a form of structured conflict management during violent conflicts, directed and overseen by the United Nations since the end of World War II. After more than 75 years of peacekeeping efforts by and through the UN, peacekeeping missions now comprise a primary international response to civil wars and armed interstate conflicts, once the active hostilities have subsided.

UN peacekeeping is authorized by the Security Council, and it communicates to the fighting parties the interest of the international community in the end of hostilities. Peacekeeping may be tailored to the specific situation and needs, using both military and civilian resources to achieve the mission’s stated goals and strategic objectives. See Doyle & Sambanis (2006), and Hegre, Hultman & Nygård, (2019). Typical tasks of peacekeeping missions include the separation of warring parties, monitoring of ceasefires, and management of “buffer zones” between the parties.

The Intersection of Mediation and Peackeeping

Clayton and Dorussen review recent research on the intersection of mediation and peacekeeping, arguing that while peacekeeping efforts may undermine mediation, the two generally complement one another and may reduce the duration of conflict. See Grieg & Diehl (2005) regarding negative interactions between mediation and peacekeeping. Others report generally more encouraging, positive results from the combination of approaches in active conflicts. See Beardsley, Cunningham & White (2019) and DeRouen & Chowdhury (2018). Finally, other researchers have found that the duration of a conflict can be shortened through the deployment of peacekeepers while a negotiated settlement is developed through mediation. Kathman & Benson (2019).

Ultimately, Clayton and Dorussen contend that mediation and peacekeeping complement one another and both assist in ending armed conflicts. Negotiated settlements designed to end violent conflicts often fail. However, conflicts ebb and flow in terms of violence and hostilities, and it may be difficult to assess the effectiveness of any tool during that dynamic process of escalation and de-escalation.

The Study: Methods and Data Sets

To assess the relative importance of mediation and peacekeeping, Clayton and Dorussen evaluate conflict data generated by the Uppsala Armed Conflict Data Project. See Pettersson & Wallensteen, (2015). They examine (1) peacekeeping mandates, (2) types of conflict, and (3) periods of time before turning to the statistical significance of both peacekeeping and mediation in ending hostilities. Because of the possibility that both approaches could reach significance without actually contributing to the reduction or end of hostilities, the authors use “simulations to provide a counterfactual analysis showing their substantial impact on the frequency of conflict.”

The authors also used binary time-series cross-sectional (BTSCS) models with “conflict year” as the unit of analysis. These models evaluate factors influencing the length of a conflict. Their research accounts for selection effects, possible reverse causality, and differences between inter- and intrastate conflicts. Finally, the researchers use a counterfactual analysis and specific selection models to hypothesize how much conflict would have occurred without mediation and peacekeeping in ex post conflicts where both tools were critical to the end of the conflict.

Various data sets were used to identify dependent and independent variables, including the use of six binary variables applied to each conflict-year (no conflict management; mediation with traditional peacekeeping; mediation without peacekeeping; etc.). Clayton and Dorussen evaluate 439 instances of conflict termination between 1946 and 2013, where mediation was present in 25% of conflicts before 1989 and 35% of conflicts post-1989.

The Takeaway: Peacekeeping Efforts Reinforce Mediation in the Reduction of Armed Conflicts

Mediated agreements can be strengthened through the strategic use of peacekeeping efforts. Clayton and Dorussen argue that peacekeeping reinforces mediation because (1) mediation is far more difficult when active hostilities endure; (2) peacekeeping can stabilize a volatile situation; (3) cooperation between peacekeepers and mediators can enhance understanding and outcomes; and (4) peacekeepers can monitor and support compliance with a negotiated settlement.

Clayton and Dorussen found that mediation positively influences the likelihood of both interstate and intrastate conflict termination, whether or not it is coupled with peacekeeping. Peacekeeping, on the other hand, only significantly increases the likelihood of termination when used together with mediation.

Thus, the creation, implementation, monitoring, and success of a mediation agreement can be actively supported by an effective peacekeeping operation. Mediation and peacekeeping complement one another, and peacekeeping can be used specifically to bolster the effectiveness of a mediated settlement.

Citation

Clayton, G., & Dorussen, H. (2022). The effectiveness of mediation and peacekeeping for ending conflict. Journal of Peace Research, 59(2), 150-165. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343321990076

Explore Mediation

Schedule a Call with Dr. Earwicker Today!

Learn MoreClinical Mediation and Counselor Education

Conflict resolution, mediation and counseling go hand-in-hand; college and university counseling programs can further integrate the mutually beneficial skills of counseling practice and various forms of dispute resolution, including mediation.

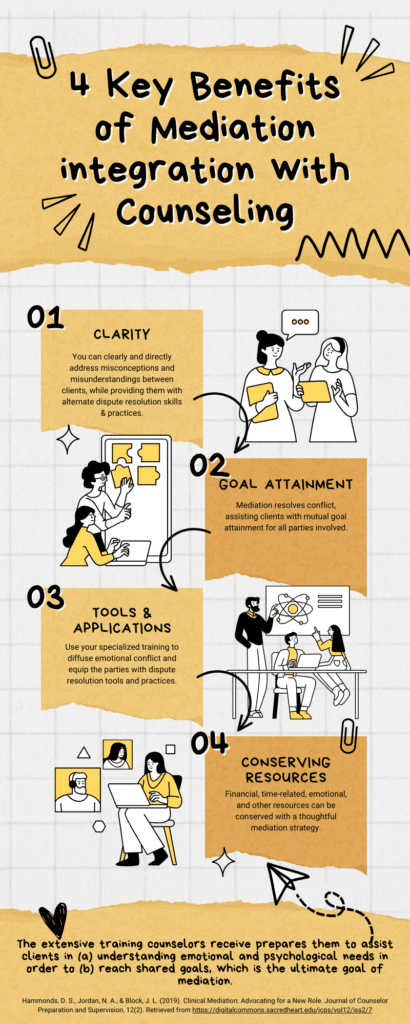

In their 2019 article, “Clinical Mediation: Advocating for a New Role,” Appalachian State University authors Dominique S. Hammonds, Nickolas A. Jordan, and Jessica L. Block argue that counselor training programs often fail to provide adequate training for mediation and counseling. This is especially true when evaluating, understanding, and dealing with emotions shaping conflict and those that prevent mutual goal attainment. The authors contend that mediation and counseling should be co-taught, in order to enhance both practices.

Mediation and Counseling: The State of Education

Despite the obvious connections between mediation and counseling, practitioners who offer both services are exceptions to the rule. As the authors point out, though, counselors are uniquely positioned with their skills and training to provide effective mediation, due to their “counseling skills and increased emotional intelligence.” n.p.

The intersection of mediation, education, and counseling practice is one that has not been fully explored in counselor education programs, but it is an area that warrants further development and exploration by practitioners and educators alike.

The Relationship Between Mediation and Counseling

Defining Mediation

As a form of dispute resolution, mediation is less formal than the process of arbitration (often used in lieu of litigation in the courts), but more structured than informal methods of resolving family, employment, community, or other types of disputes. Mediation involves a neutral third-party mediator who facilitates discussions and negotiations used to resolve any number of disputes.

The ultimate goal of mediation is a mutually beneficial resolution of disputes and mutual goal attainment. Unlike the adversarial court process, mediation offers parties a chance to discuss and choose their own outcomes, rather than deferring those decisions to an arbiter, judge, or other third party. Finally, unlike other forms of Alternate Dispute Resolution (ADR) like arbitration, mediation offers a neutral third-party mediator who has no stake in the outcome and final resolution, though certain ethical considerations apply to the process of mediation.

Many mediators are practicing attorneys, though their training in legal systems and adversarial processes contrasts strongly with counseling education and specialty areas in counseling such as addictions, clinical mental health, rehabilitation, marriage/couple/family, and others. Counselors and other non-attorney practitioners are uniquely suited to provide an alternative perspective and approach in mediation.

The Benefits of Mediation

Mediation offers a number of benefit to parties engaged in this form of alternate dispute resolution, including each of the following:

- Clearly and directly addressing misconceptions and misunderstandings;

- Seeking resolution of conflict, including mutual goal attainment;

- Diffusing emotional conflict and equipping the parties with dispute resolution tools and practices; and

- Conserving resources (financial, time-related, emotional, and other resources) that would otherwise result in lengthy, costly court battles, emotional distress, and other negative outcomes.

Emotional Intelligence, Mediation and Counseling

The authors contend that the extensive training counselors receive in Mayer, Caruso, and Salovey’s four branch model of emotional intelligence prepares them to assist clients in (a) understanding emotional and psychological needs in order to (b) reach shared goals. This is the goal of mediation: individual and mutual understanding that leads to resolution of conflict and mutual goal attainment.

Emotional intelligence, defined originally by Salovey and Mayer, conceptualizes the way individuals problem-solve and understand the world around them (one’s “ways of knowing”). The four branch model recognizes an individuals’

- perception of emotions;

- use of emotions to facilitate thought;

- understand emotions; and

- manage one’s own emotions and those of others.

The authors note the progressive, developmental nature of this model. At the same time, less is known about the abilities and mental states that support emotional intelligence.

Nevertheless, perceiving emotions through vocalizations, expressions, behavior, and forms of communication reflects one’s perception of emotions. Similarly, relating emotionally to the experiences of others reflects the ability to understand emotions, and understanding the meaning, context, and impact of emotions represents the use of emotions to facilitate thought. Finally, evaluating and managing strategies to handle emotional responses (by one’s self and others) demonstrates an ability to manage emotions effectively.

The Takeaway: Mediation, Academic Counseling Programs, and Counseling Practice Go Hand-in-Hand

Ultimately, the goals of mediation, counselor education, and the practice of counseling align well, and skilled counselors should deepen their knowledge and skill in dispute resolution practices and methods, including mediation. The symbiosis between mediation and counseling should translate into intentional curricular shifts that require dispute resolution practices and methods in counselor education. Practitioners, likewise, should explore mediation and the possibility of integrating mediation into their own practices, either directly or through professional partnerships that facilitate dispute resolution outside of therapy. Clients benefit from a counselor’s added skills in mediation and alternate dispute resolution, and mediation can support therapeutic work when legal or other issues outside of counseling can be addressed systematically and intentionally through mediation.

Citation

Hammonds, D. S., Jordan, N. A., & Block, J. L. (2019). Clinical Mediation: Advocating for a New Role. Journal of Counselor Preparation and Supervision, 12(2). Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/jcps/vol12/iss2/7

Explore Mediation

Schedule a Call with Dr. Earwicker Today!

Learn MoreAcademic Mediation Research Review

Integrating Schools of Thought – VirNet Mediation